Anko sweet red bean paste culture has deep roots in Mie Prefecture.

The spirit of a long-established anko house, refusing to be swayed by trends and taking pride in its own individual aesthetic.

———The way of Mie is the way of mochi (glutinous rice cake). At the end of the Ise Highway, there is an anko (sweet bean paste) maker.

Since long ago, the Ise Highway has been the path of pilgrimage to the Ise Shrine. Due to this influence, in each area of the prefecture, mochi culture remains to this day. This time, I paid a visit to a long established anko (sweet bean paste) maker to learn about modern mochi culture.

For this report, I spoke with (from the left) Mr. Yukio Yoshimura, his younger daughter Hiroko, and his oldest son Shuichi.

To begin with, what kind of work goes on in an anko workshop?

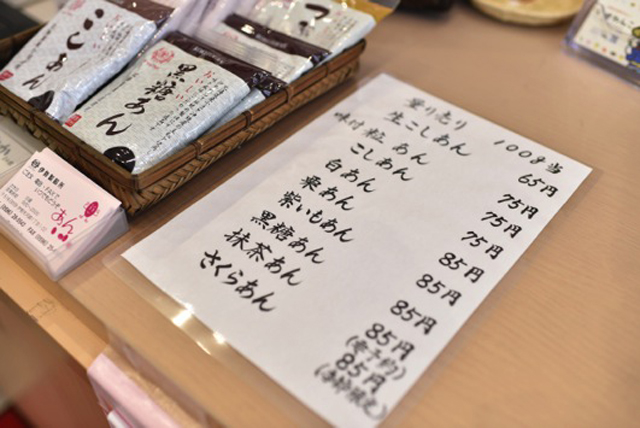

At this workshop, adzuki beans, the main ingredient in anko, are prepared and processed into chunky tsubuan and smooth koshian, which is then packaged and sold. They have products intended for end consumers as well as products intended for sweets makers and traditional Japanese confectioners. They have also been doing bulk sales by weight at the front counter since long ago.

Hiroko recalls “We sometimes had to mind the shop when we were kids. It’s an anko shop, so I was sometimes called ‘An-Chan’.”

———Unswerving, so they say

I had heard that this shop enjoys an excellent reputation among large sweets manufacturers and traditional Japanese confectioners alike. This is due to the great care they take in the selection and handling of their raw materials, as well as their dedication to preserving their traditional flavor.

“I hate when things aren’t done right.” declares Yukio.

I haven’t heard such sharp words in a long time. This report is a testament to these words, but I’d like to get a clearer picture of what they really mean.

———No regrets, this stance of using only the finest aduki beans is the talk of the adzuki producing regions.

Yukio’s parents established the business in the city of Matsusaka in 1924. In 1955, Yukio opened a second location in nearby Ise, and has been protecting the brand ever since.。

On reason this shop’s name is so highly praised is the strictness with which its ingredients are selected. It uses only the freshest adzuki beans from the Tokachi region of Hokkaido. These beans are sold under the brand name ‘Miyabi’, which is renowned for its excellent quality and is used by the finest traditional Japanese confectioners.

“We are famous in Hokkaido for being about the only small town anko maker that has no qualms about using such high quality adzuki.” Hiroko boasts.

Her pride in the family business is can be heard in her voice.

As I look around, I’m surprised to find much larger equipment than I had expected on the work floor. In order to increase production, they had this equipment custom made about 20 years ago.

“There are only a few places in the country that make anko using only this sort of equipment.” Hiroko explains.

Using today’s koshian (smooth sweet bean paste) as an example, the foreman explains the production process. Work begins at 5:30 in the morning. The beans are washed, then simmered for about three hours in the same bronze pot they’ve been using since the business was founded. A worker frequently stirs the beans and checks their progress.

Once they are done cooking, in the case of koshian, the skins are separated from the flesh of the beans.

In recent years, some producers have stopped taking the step of removing the skins, instead grinding the beans into a powder, skins and all. When asked about this production method, Hiroko flatly states,

“We do NOT add the skins”.

In other words, they have not diverged from their traditional flavor.

This is why the extra step is taken.

In the past, famous traditional Japanese confectioners have reached out to them, saying “Koshian made without skins is very hard to find.”

Separated from the skins, the flesh of the beans is cooled in a large water bath. The material that floats to the top is removed and discarded. The remaining adzuki is placed in a specially designed machine where it becomes unsweetened, powdery “nama’an”. This nama’an is the main ingredient in koshian.

“There are many steps involved in making nama’an.” says Hiroko.

Once the nama’an is ready, it is mixed with sugar and water and is blended for about one hour. The resulting paste is called katouan (sugared bean paste). This isn’t a word one often hears in daily life, but, because it refers to a mixture of nama’an, sugar and water, here in the anko workshop it is bandied about quite naturally. Whether making smooth koshian or chunky tsubuan, it all starts with the mixture of nama’an, sugar, and water that is katouan.

One cycle of this process yields about 200 kilograms of katouan. They produce one ton per day, so this process is repeated five times daily.

The finished katouan is put into a copper pot which is then lifted with a hoist and dumped into a filler machine. At this instant, the delicious aroma of freshly made anko fills the air.

Having never seen this before, the sight and smell of this scene makes a lasting impression on me.

The anko in the filler machine is pumped into packages, and just like that, the final product is complete.

———The man who resisted the “Less Sweet” trend

About 20 years ago, there was a trend among traditional Japanese confectioners to make their products less sweet. Many confectioners and anko makers were swept up in this trend. They used less sugar and reduced the sweetness of their wares. However, Yukio didn’t approve of this movement.

“I made the decision to continue as we have always done, and to produce the same taste as always. Even now, we remain true to this principle. We like the genuine article.”

There was a time when the widespread use of imported sweeteners gave rise to price wars which made sales difficult, but at that time, an appreciation for the flavor of the real thing made in the old way provided support for Yukio and his methods.

I enjoy some special koshian as I learn the particulars of anko production.

I can sense the high quality sugar in its wonderful sweetness.

It has a silky texture, and the rich mellow flavor fills my mouth. The sweetness isn’t cloying at all.

We only use the finest sugar, so it isn’t cloying.” says Hiroko.

If artificial or processed sweeteners are used in an effort to reduce the amount of sugar needed, the resulting sweetness lingers in one’s mouth. However, sweetness born of fine quality ingredients fills the mouth instantly, then fades away cleanly, Hiroko informs me.

“That way, you want to eat more. Back when everyone was going on about less sweetness, the long established traditional Japanese confectioners didn’t change one bit. They continued to produce the same flavors they had always done.” Yukio says.

“I hate it when things aren’t done right.”

Yukio’s words come floating back. In truth, it’s not just about doing things right. This unwavering man, thanks to his tongue and his wisdom, knew that there was no reason to change his methods and refused to be swayed by trends. Thus he can declare with pride, “This is the taste of the genuine article!”

This DNA has been passed to the next generation.

———”An-Chan” has become an adult and, taking pride in the family business, she strives to expand it.

After coming to the workshop, Hiroko soon became the head of the sales department, even going alone to Tokyo to set up booths at trade shows.

At those shows, her booth was often placed right next to the booth of a large anko maker, she says.

“No matter what the situation was, I continued to confidently present our products to the buyers who attended the shows. More than the large makers, I made sure to stand out in front of my booth, stopping as many buyers as I could. I couldn’t let the big guys win, I thought.”

People who have a family business understand. When you are young and you watch your parents and relatives working up close, you often develop stronger feelings about that work than other people have.

Hiroko tells me “Recently, our products have become more highly praised than the nama’an of large anko makers.”

In Hiroko, who worked tenaciously for many years to promote her unyielding father’s flavors, I can sense the same unyielding strength.

Yukio will turn 85 years old this year.

“When I was younger, I could carry 100 kilos of stuff, but now, my hands are full just getting myself around.” he says.

“Nah, he’s still doing fine. Dad is in charge of all the accounting. He’s mastered the computer, and even does some programming.” Hiroko tells me.

“I figure that way, they’ll let me keep working forever!” Yukio says.

“That’s right!” Hiroko laughs.

As Hiroko laughs, Yukio smiles warmly. This sort of conversation seems just right for a pair of coworkers cooperating to make anko.

Anko which has sweetness, but a clean finish.

In preparing this report, I sense a similar flavor in the conversation of this pair, reminiscent of the sweet, happy feeling one gets after eating anko.

December 11, 2017

Produced for Web Magazine OTONAMIE

By:Yuji Miyazawa (Writer)

With the Cooperation of:

Iseseiansho Corporation

Mie Ken Ise Shi Kawasaki 1-1-22

Tel 0596-28-5543

HP http://iseseian.jp